Siri’s Descendants

How intelligent assistants will evolve

The internet swarms with intelligent assistants.

What started as an isolated app on the iPhone has evolved. Intelligent assistants constitute an entirely new network of activity. No longer confined to our personal computing devices, assistants are being embedded within every object of interest in the cloud and the internet of things.

Assistants have become far more nimble and lightweight than their monolithic ancestors; much more like smart ants than people. As specialists, they work cooperatively — sometimes competitively — to find information before people even realize they need it.

People are still communicating directly with assistants, although rarely using natural language. Implicit communication dominates. Assistants respond and react to our subtle contextual interactions, and to each other, within vast informational ecosystems.

This is how intelligent assistants evolved…

The Fate of Today’s Intelligent Assistants: More of the Same

Intelligent assistants like Siri, Google Now, and Cortana are so young, it’s difficult to imagine how they will change; harder still to imagine how they might die. But if history is a guide, inevitably they will give way to entirely new product forms.

When pundits and analysts discuss the future of intelligent assistants, they typically extrapolate from the conceptual model of today’s assistants. The next version is always a better, smarter, faster version of the last, but it’s still the same species.

But what can we learn about the future of assistants based on what Siri hasn’t become?

As detailed in Bianca Bosker’s Inside Story of Siri’s Origins, when Apple acquired Siri, the scope of the product’s capabilities actually narrowed. Using the audacious vision of Siri’s founders as a palette, Apple selected a narrower set of product values on which to focus.

The same force that reduced the scope of Apple’s Siri from a “do (everything) engine” to a much more narrow product is what keeps incumbents rooted to the existing concept of intelligent assistants.

The Evolution of Assistants In Underserved Areas

When forecasting change, it’s not so much what the technology of intelligent assistants might support as what product leaders choose to pursue. While many brazenly contest existing markets, product leaders look for new, underserved areas of the landscape to exploit.

The future always surprises, but we can predict the trajectory of change by examining which product values are being embraced, and which ones are neglected.

If you believe the internet abhors a vacuum, then you’ll understand how intelligent assistants will evolve to inhabit these underserved niches.

Charting the Evolutionary Path

Just like directions on a compass, the following maps point to fertile areas of the landscape, where new product forms may evolve.

Note that product values are often coupled due to technological constraints. Decisions along one axis constrain possibilities along another. These couplings are explored at a high level in two-dimensional perceptual maps: interface and distribution; knowledge and tasks; organization and autonomy.

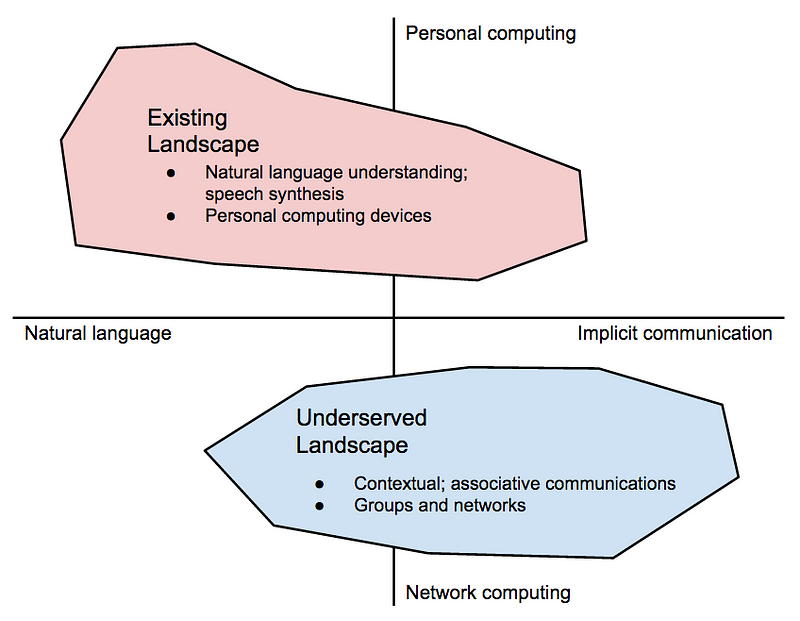

Interface and Distribution

No longer confined to our personal computing devices, assistants are becoming embedded within every object of interest in the cloud and the internet of things.

People are still communicating directly with assistants, although rarely using natural language. Implicit communication dominates. Assistants respond and react to our subtle contextual interactions, and to each other, within vast informational ecosystems.

The aspects of assistants that are most obvious to end-users are the interfaces (how we interact with assistants) and their mode of distribution (where people experience assistants).

Today’s assistants are overwhelmingly focused on natural language interfaces. The experience of assistants that speak our language and communicate like a person has come to define the product class.

This focus on natural language interfaces has biased the distribution of assistants to personal computing devices. Intelligent assistants embody any device capable of receiving and synthesizing speech, such as smartphones, desktops, wearables and cars.

The underserved areas of this map involve communications that are not based in natural language. For example, there’s much to learn about our needs and intentions based on context (where we are and what we’re doing) as well as on our ability to make inferences based on the associations that people form (for example, the way that people organize information or express their likes and dislikes). Natural language is but the tip of this much larger iceberg of communications.

These alternative forms of communication not only support individuals, but also groups. While it’s difficult to understand a room full of people all speaking at once, it’s much easier to understand their collaborative communications, such as their documents, click-paths, and sharing behavior. Therefore, the options for distributing intelligent assistants that use these implicit forms of communications are not constrained to personal computing devices, but may leverage entire networks.

As a simple example, consider how you highlight your interests as you browse a website. You focus your attention on specific pages within the site. You follow your interests as you navigate from page to page. You may choose to share some information within the site with a friend. Now compound this behaviour across every visitor to the site.

Intelligent assistants that are associated with the website can respond to these interactions to help the right information find each individual, as well as adapt the website to better address the needs of the entire group.

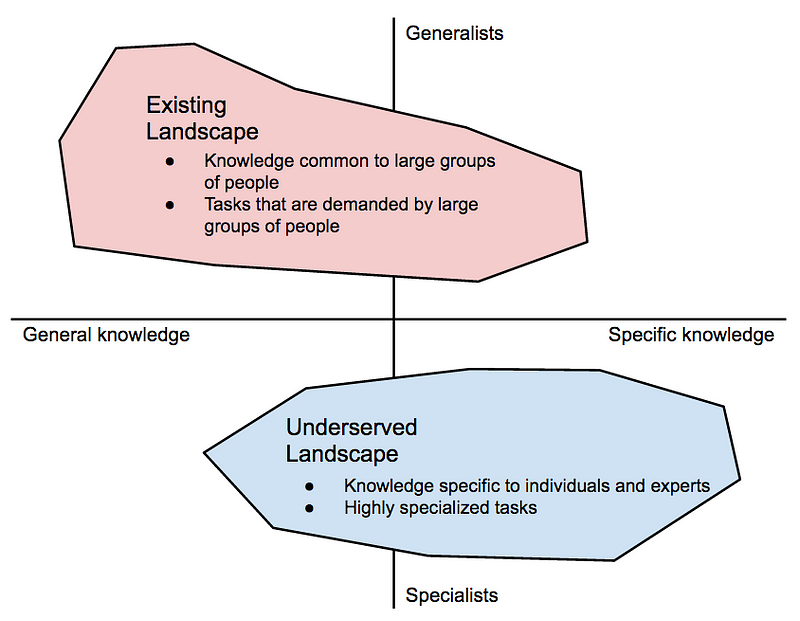

Knowledge and Tasks

As specialists, these machines have become far more nimble and lightweight than their monolithic ancestors; much more like smart ants than people.

Intelligent assistants require domain knowledge to perform their tasks. For example, if your assistant is giving you advice on how to navigate to work, it needs to have knowledge about the geographic region (general knowledge) and knowledge of how you typically navigate (specific knowledge).

Tasks and knowledge are tightly coupled. As you increase the specificity or the personalization of the tasks, the underlying knowledge needs to be far more specific to support it.

Within this frame, today’s intelligent assistants are unabashedly generalists. They’re targeted to the masses. Like trivia buffs, their knowledge of the world is broad enough to be relevant to the needs of large groups of people, but few would describe them as experts. Their tasks are similarly general: retrieving information, providing navigational assistance, and answering simple questions.

The underserved landscape points to much more specific domains of knowledge, the purview of experts and our individual subjective knowledge. Assistants that become experts necessarily take on a smaller scope of activities. They can’t know and do everything, so they become smaller in scope.

The landscape for specific tasks is similarly underserved. Every website, every service, every app, and across the internet of things, everything embodies a collection of tasks that may be supported by intelligent assistants. In this environment, the metaphor of personal assistants quickly fragments into systems that are much more akin to colonies of ants.

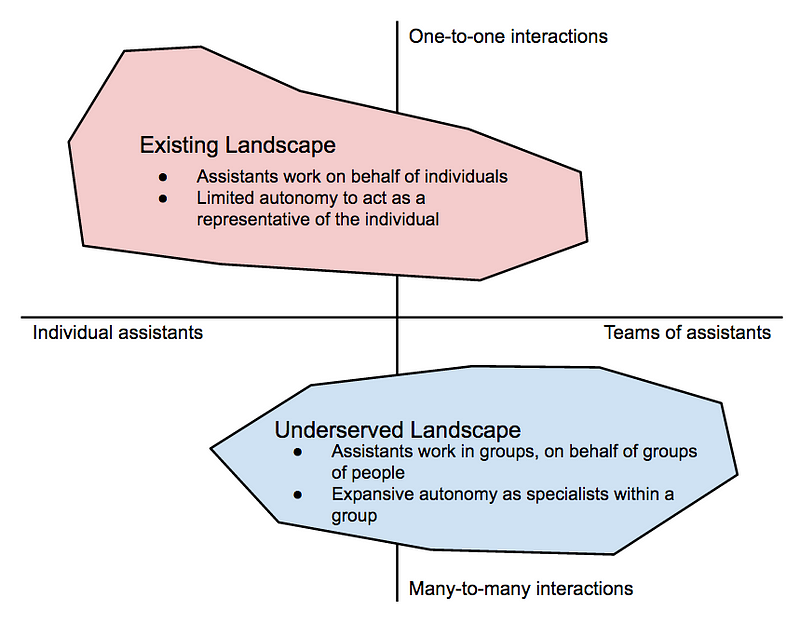

Organization and Autonomy

As specialists, they work cooperatively — sometimes competitively — to find information before people even realize they need it.

The organizational structures in which assistants are placed constrain their autonomy. When embedded within a personal computing device, an intelligent assistant is directed to one-to-one interactions with their master.

Since these assistants are acting as an agent of the individual (and only that individual), their autonomy is necessarily limited. While you might be comfortable with your executive assistant drafting your messages, I suspect you’d be less comfortable with your smartphone doing the same.

In stark contrast, the underserved landscape embraces groups, both in terms of the interactions and the organizational structures.

As assistants get smaller and more specialized, they can become agents of much more specific objects of interest, like places, websites, applications, and services. Within these smaller realms of interest, their autonomy can be much more expansive. You might not want a machine to act as your representative, but you would probably feel more comfortable if it represented only the website you’re visiting.

With increased autonomy, the barriers to many-to-many interactions are removed. These small assistants can be organized as teams into networks, much like the documents that comprise a website, collaborating in an unfettered way with other assistants and the people that visit their realms.

When Will The Future of Intelligent Assistants Arrive?

This market analysis highlighted a number of underserved areas as fertile ground for the evolution of intelligent assistants. It grounds this vision in predictable market dynamics. There’s obviously no shortage of space or product values to explore in these underserved areas.

It says nothing, however, about when this future will arrive. Product evolution, like biological evolution, needs time and resources. The most important resource is the dedication of product leaders with the drive to pursue these new opportunities.

Are you an entrepreneur, technologist, or investor that’s changing the market for intelligent assistants? If so, I’d love to hear your vision of the future.